Inside Virginia's Push to Become the Top State for Talent

Talent attraction, educational alignment, reducing barriers to employment among key issues

Virginia’s long-held reputation as a top state for business is based on its strong economy, robust infrastructure, innovative incentives and programming, and, increasingly, its highly skilled workforce. To remain atop state business rankings and compete for projects, the Commonwealth is committed to also becoming America’s Top State for Talent.

With its newly established Talent and Workforce Strategy team in place, VEDP is prepared to take a leading role in the Commonwealth’s quest to top the talent rankings, but achieving this ambitious goal will require a cross-sector, cross-agency effort.

Together, VEDP and its partners will take a multifaceted approach to address the many dimensions of Virginia’s talent pool and pipeline. Virginia’s plan to become the Top State for Talent includes three core talent strategies: attract and retain talent, promote alignment between education and employment, and reduce barriers to employment.

Winning the Talent Wars

Demographic trends are making attracting and retaining talent an increasingly difficult and complex goal. Population aging and lower birth rates are leading to a shrinking workforce, both for Virginia and the rest of the country. Congressional Budget Office data indicates that the share of the U.S. population over the age of 65 rose from 12.4% in 2007 to 17.9% in 2024. It is expected to top 20% by 2035.

“We’re going into a bit of an arms race,” said Hamilton Lombard, estimates program manager in the Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service. “I’ve heard it described as a war for talent — when you have less growth in the workforce, you’re competing harder for it. These points are going to become increasingly salient over the next five to 10 years.”

In other words, what had previously been a skills problem is becoming a people problem. What does the workforce of the future look like with Virginians having fewer children — and what does it look like when North Carolinians and Tennesseans and Marylanders are having fewer children as well? How can states work most effectively to attract talent to their workforce? The states that figure this out most effectively will position themselves to win the talent war.

“We’re at a point in Virginia and nationally that over the next seven to 10 years, we’re not going to grow anymore unless we are attracting new workers and residents. It’s just an aging population,” Lombard said. “This ability to attract and retain talent becomes more and more important, because you’re not having more people turning 18 and coming into the workforce. If you want to maintain your workforce, you’ve got to attract or retain.”

To keep Virginia workers and students in the state and convince residents of other states to relocate to the Commonwealth will require creativity and storytelling. A large part of this will center around why Virginia is a great place to live, work, and play. Localities and the state as a whole must market the Commonwealth’s quality of life — positioning Virginia as a place workers want to live.

The Roanoke Region engages “talent ambassadors” to tell their story. These 40 locals connect with new arrivals, sharing their regional expertise and personal experience to convince transplants to remain long term.

“We’ve got this brand that people know as an outdoor destination. But when they come here, they also need to know we have good jobs and places for them to live so they can get ingrained in the community quickly,” said Julia Boas, director of business investment at the Roanoke Regional Partnership. “Now we focus a lot of our specific talent attraction marketing efforts around removing barriers to those things, creating user-friendly resources for people, and then driving traffic to those resources so that people can see themselves here.”

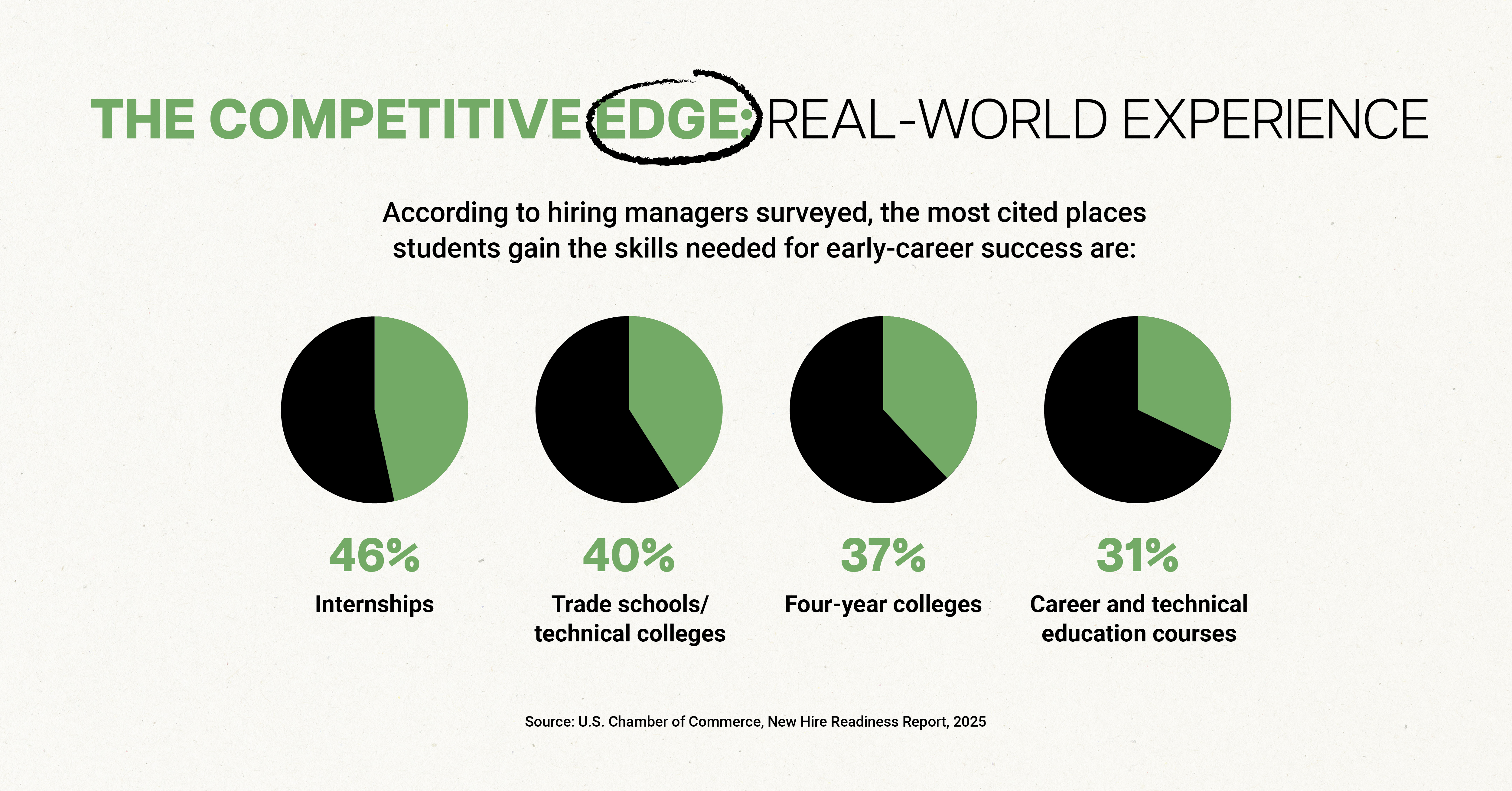

Beyond promoting the Commonwealth’s quality of life, Virginia is committed to implementing policies and programs that encourage workers to remain in or relocate to the Commonwealth. A partnership between VEDP and the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV), the Innovative Internship Program is providing $14.5 million in funding for fiscal 2026 to increase internships and other work-based learning opportunities. By connecting students with employers while they are still in school, the program aims to increase the number of students who take jobs within the state post-graduation.

Helping Education Meet the Needs of Industry

Stuart Andreason is executive director of programs at the Burning Glass Institute, an organization that conducts research at the intersection of learning and work. Before that, he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Virginia and spent time working in economic development in Greene and Orange counties, north of Charlottesville, in the late 2000s — an experience that has informed his career since then.

“There was a lot of work going out for economic development projects that wasn’t landing, because there wasn’t a great talent story at the time,” he said. “The jobs that were coming in didn’t feel like the types of economic development wins that the communities wanted.”

One concept Andreason highlighted is that of the “Learning Society,” a departure from the way the United States educates its children, which he called the “Schooled Society.” Currently, education is delivered through schools and focuses on children, measuring progress by years of schooling and attaching employment and social mobility to credentials. This model does a lot of things well, notably making universal education a right while driving prosperity and boosting social mobility. But it also offers little integration between education and career and limited opportunity for continued learning.

The Learning Society, in contrast, provides a structure for learning across a person’s lifetime, building on the foundation laid through schooling. This type of setup ensures that each job transition is an opportunity for economic mobility, gives workers agency over their career progress, and enables them to stay relevant even as jobs shift. Similar ideas have described a highway model for education, with workers using on- and off-ramps to navigate jobs and necessary training.

The Virginia Office of Education Economics (VOEE) plays a key role in the Commonwealth’s efforts to align education and industry. VOEE, the first state office of its kind, leverages data to inform education and workforce programming, policy, and partnerships across Virginia. The Workforce Credential Grant (also known as FastForward) and the G3 program, two impactful Virginia higher education funding streams, rely on VOEE analyses to identify programs that align to high-demand occupations. Virginia higher education institutions also use VOEE data as part of their new program approval process. VOEE provides labor market and education data to demonstrate whether there is a need for a program.

As an apolitical organization, VOEE (as well as VEDP) is positioned to provide reliable, consistent, and unbiased information across gubernatorial and legislative changes.

“VOEE has a structure where we’re in an authority that is not beholden to an administration or the General Assembly,” VOEE Executive Director Wendy Kang said. “Being at VEDP, we’re in a unique situation where we can transcend administrations and changes to be true to our purpose. You need that stability to look at data objectively.”

Getting Virginians off the Sidelines

Even with the people and training programs in place, Virginia may still struggle with a labor shortage if barriers keep skilled workers out of the labor force. The Commonwealth recognizes that to be the Top State for Talent it must also address those factors that inhibit people from working.

Child care availability is another barrier that prevents many workers, particularly women, from participating in the workforce — an issue exacerbated when nearly 16,000 child care centers and licensed family child care programs across the country closed permanently during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a 2020 U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation study, more than half of working parents (58%) reported leaving work during the pandemic because they were unable to find child care solutions that met their needs. A 2021 Pew Research study also noted “taking care of home/family” as a primary reason women left the workforce, with 79% of mothers citing that factor and 23% of fathers (up from 4% in 1989 and now the second-largest factor, behind only illness and disability).

Even when parents can find a provider, Child Care Aware of America data places the national average annual cost of child care at more than $13,000 per child, making it more cost-effective for many parents to stay home rather than pay for care.

Another common barrier to employment is transportation, particularly in rural areas. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, citing a South Carolina Department of Employment and Workforce survey from 2022, nearly 20% of individuals who were able to work but not currently working cited transportation as a barrier.

Housing costs are also a significant issue. According to a 2025 report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there are no states, metropolitan areas, or counties in the United States where a worker earning the federal or prevailing state and local minimum wage can afford a modest two-bedroom rental home.

“In the last decade, we’ve seen the price of existing home sales double,” Lombard said. “That really affects the workforce, particularly the younger part that’s trying to buy their first home. In many of the major job centers across the country, home ownership has basically become out of reach.”

To be the Top State for Talent, Virginia must engage all of Virginia’s talent, including vulnerable populations, but these Virginians are particularly sensitive to workforce barriers. Virginians with disabilities are more likely to have issues with transportation, and workers with a history of substance use or involvement with the justice system have specific hurdles to overcome before participating in the workforce. Workers who struggle with behavioral health issues are another key group. Not only are they an important talent pool for Virginia’s economy, these individuals are more likely to keep up with treatment when they are employed.

Workforce Development Is Economic Development

Andreason highlighted the nuances of building and promoting a strong talent base as part of a holistic economic growth strategy. “How do you align talent strategies with economic development strategies?” he asked. “How do you understand what types of talents make a place competitive, and what can you do to invest in that?”

Becoming the Top State for Talent is fundamental to Virginia’s economic development. Virginia’s most valuable economic resource is its people. In the face of a shrinking workforce, the Commonwealth must ensure that its workers have the necessary skills and access to contribute to the economy, while also attracting new workers to the state. Virginia’s plan to be the Top State for Talent will require collaboration among all of its education and workforce partners, and it will include every worker — or potential worker — in the Commonwealth.